The Bells of Weber State

An Ogden campus landmark turns 50.

Karin Hurst, Marketing & Communications

On Christmas Eve 1945, a weary World War II paratrooper from the Army 82nd Airborne Division battled tangled ticket lines at crowded train terminals and circuitous detours on an ill-conceived mission to reunite with his family in Ogden, Utah. Four days into his nine-day leave, the young soldier had only made it from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to Cincinnati, Ohio.

Homesick and defeated, he stepped outside the depot to stretch his cramped legs. While moon-kissed snowflakes fluttered to earth, his eyes locked on an illuminated nativity scene a short distance away. As he trudged closer, a magnificent chorus of carillon bells pierced the evening solitude. The otherworldly toll of an ancient carol soothed Pfc. Dean W. Hurst’s soul and steeled his resolve to find joy and meaning in each new experience.

A Lasting Impression

The carillon is an extraordinary musical instrument comprised of at least 23 cast bronze bells, tuned to produce concordant harmony when multiple  bells are sounded together. For more than five centuries, the carillon has been a voice for humankind: tolling warnings, mourning defeats, celebrating victories and announcing news. Carillons are typically installed in a belfry, a tower that is attached to a main building, or a free-standing structure called a campanile.

bells are sounded together. For more than five centuries, the carillon has been a voice for humankind: tolling warnings, mourning defeats, celebrating victories and announcing news. Carillons are typically installed in a belfry, a tower that is attached to a main building, or a free-standing structure called a campanile.

Dean Hurst’s memory of yuletide bells in Cincinnati resurfaced in 1968 as he studied a Weber State campus master plan. One year earlier, he had been hired as the school’s first, full-time executive director of Alumni Relations and the newly established college development fund. Through his energetic fundraising efforts and extensive involvement in the community, Hurst became well-acquainted with an Ogden couple and their affinity for Weber.

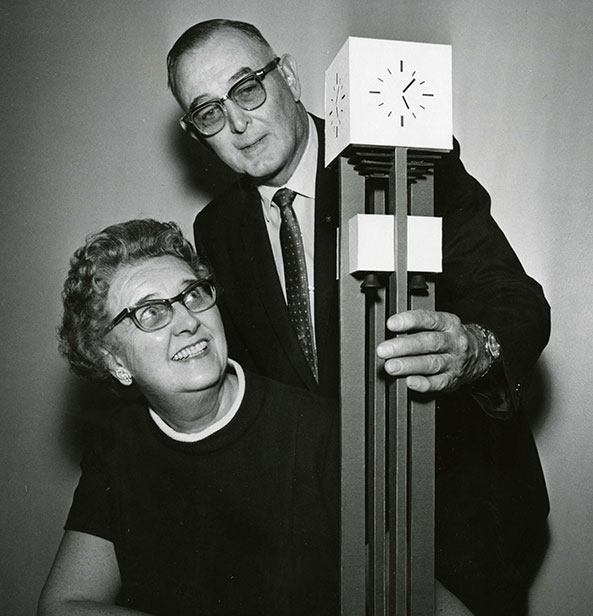

Donnell B. Stewart served as student body president during the 1925–26 academic year. After a lengthy military career, he returned to Weber State in 1966 for a business administration degree. His wife, Elizabeth Dee Shaw Stewart, a granddaughter of Ogden pioneer industrialist Thomas D. Dee, attended high school at Weber Normal College and stayed when the school became a junior college in 1922. She worked at Weber as the assistant registrar and, later, as secretary to President Aaron W. Tracy. While temporarily placed in charge of the college library in 1931, she was asked to teach two English courses.

At 35, Elizabeth underwent life-saving surgery that left her unable to bear children.

At 35, Elizabeth underwent life-saving surgery that left her unable to bear children.

“It was a dreadful shock to me, for it meant that the family I had always hoped to have would never become a reality,” she recorded in her memoirs.

The antidote to her profound sense of loss, she would discover, was to lose herself in the service of others.

Like Music to a Development Officer’s Ears

After establishing a music scholarship in honor of Elizabeth’s mother in 1964, the Stewarts donated a series of what they considered to be “small gifts” to Weber — a Jeep for archeological trips, equipment to measure atomic power for the physics lab.

“Then one day I said to Dean, ‘Isn’t

there something the college needs that

is a little more acknowledgeable than what we have done?’” Elizabeth noted in her journal.

Hurst consulted a two-year-old campus plan sketch and spotted an inconspicuous shape he was told could represent a clock or bell tower.

“I immediately thought of the carillon in Cincinnati and envisioned something similar at Weber, a kind of central landmark that would rise above campus and be seen from many vantage points in the community,” he said.

Hurst ran the idea past then-President William P. Miller, who recalled listening to the cheerful clang of the carillon in Hoover Tower at Stanford University, where he pursued his doctorate. He encouraged Hurst to seek funding from the Stewarts.

“I made a rough sketch of what I thought a bell tower might look like and arbitrarily attached a $50,000 price tag,” said Hurst.

While the idea immediately appealed to Elizabeth, who loved music and had studied pipe organ with a renowned professor at Columbia University, Hurst’s subsequent research into carillons revealed an alarming disparity in the amount of money he had asked for and the actual amount it would cost to build one at Weber. Elizabeth suggested that Hurst solicit additional funding from her late mother’s charitable organization, the Mary Elizabeth Dee Shaw Foundation, which was chaired by her “Uncle Lawry” (Lawrence T. Dee), the only surviving son of Thomas and Annie Dee.

“After I extolled the virtues of the carillon, Chairman Dee scrutinized my primitive bell tower sketch and proclaimed, somewhat sardonically, ‘This looks like something off the Golden Gate Bridge!’” Hurst recalled. “My heart sank. But after a thoughtful pause, Mr. Dee continued: ‘You know, when I was a student at Cornell, I’d lie in bed on Sunday mornings and listen to the campus carillon. It always made me think of home. A carillon tower at Weber is a great idea. I say we do it!’ The rest of the board agreed, and we were on our way!”

.jpg) Well-known Ogden architect John L. Piers, a Weber College alum, designed the 100-foot-tall tower. With limited space on campus, planners chose to install a Schulmerich “electro- mechanical” carillon with 183 miniature, precision-tuned, bell-metal tone generators, which, when struck by metal hammers and amplified through Stentor speakers positioned atop the tower, produced bell tones indistinguishable from a carillon of full-sized bells, but at a fraction of the cost and weight. The instrument was played manually from a dual keyboard console located in a performance room at the base of the tower. The carillon could also be pre-programmed to play melodies automatically at certain times.

Well-known Ogden architect John L. Piers, a Weber College alum, designed the 100-foot-tall tower. With limited space on campus, planners chose to install a Schulmerich “electro- mechanical” carillon with 183 miniature, precision-tuned, bell-metal tone generators, which, when struck by metal hammers and amplified through Stentor speakers positioned atop the tower, produced bell tones indistinguishable from a carillon of full-sized bells, but at a fraction of the cost and weight. The instrument was played manually from a dual keyboard console located in a performance room at the base of the tower. The carillon could also be pre-programmed to play melodies automatically at certain times.

In addition to the electronic carillon, the Stewarts commissioned four, full-sized carillon bells, cast in Asten, Netherlands, by the Royal Eijsbouts bell foundry, along with stone clock faces and a quartet of “golden buff” brick-face pylons to match the color of other buildings on campus. To promote the area as a peaceful gathering place for campus and community, Piers added a landscaped terrace and reflecting pool, bumping the total cost of the project to $220,000.

Opening Doors for Donors

The next step was to give the tower a name. No other structure on campus had been memorialized and, according to Hurst, the Stewarts were reluctant to add their name to the bell tower.

“Elizabeth may have had an illustrious Dee family pedigree, but she and Don never sought the limelight,” he said. “They were lovely, humble, low-key individuals.”

Hurst, however, had his own agenda. He pulled the Stewarts aside and said, “I’m making you a sacrificial lamb for memorialization. I know you don’t want to, but it’ll open up doors for me as a development officer.” Turns out, Hurst was right. Don and Elizabeth Stewart’s public generosity inspired dozens of other local donors to come forward. “In fact,” Hurst chuckled, “right after the bell tower was built, Willard Eccles said to me, ‘Why didn’t you ask me to fund that bell tower? I would have done it!’”

While the project was announced to the public in March of 1970, preliminary construction didn’t begin until the spring of the following year. An onslaught of unseasonable winter storms and construction setbacks delayed Stewart Bell Tower’s grand opening until Tuesday, Dec. 14, 1971. About 200 people assembled to hear world-renowned carillonneur John Klein demonstrate the versatility of the instrument and perform a recital. Klein pronounced the Stewart Bell Tower carillon “perfectly installed and beautifully voiced.”

A Facelift for the Ages

Once tuned at the foundry, a carillon bell never needs further tuning in its tower. Bells over 300 years old sound as they did when they left their maker’s hands. Unfortunately, many structures that house carillon bells lack comparable stamina. By 2002, Weber State’s iconic bell tower was in trouble. “Water started leaking into the subbasement,” said 91¶ĚĘÓƵ Facility Management’s Patrick Malone, an electronic systems technician and bell tower caretaker for more than 32 years. “But the primary problem was that bricks began falling off.”

When then-President Ann Millner informed Hurst, his first thought was, “Oh, dear! They’re going to tear it down.” Instead, renovation crews stripped the pylons and installed new bricks; they built a large drainage system to remove excess groundwater in the plaza, replaced the four gigantic clock faces, and backlit the hands and tick marks with LED lighting so the time could be viewed at night. To emulate the beauty of the hillside above campus, landscapers also created a water feature with exposed rock and natural vegetation. But, what about the bells?

“The four large bronze bells are still up in the tower; they still play the Westminster melody and chime the hours,” said Malone. “The carillon and keyboard are over at Shepherd Union in the Stewart Bell Tower Lounge. They can still be activated to play different melodies that are amplified through the speakers,” he added.

Hurst said the new system was hard for him to fathom.

“I remember Ann telling me that we no longer needed all those bells, wires and conduits,” he recounted. “I said, ‘But how will the bell sound come from the tower?’ And she said, “Dean, it’s a new, digital world!”

A Gathering Place, Now and Always

For 50 years, Stewart Bell Tower has been an eyewitness to 91¶ĚĘÓƵ history.

For 50 years, Stewart Bell Tower has been an eyewitness to 91¶ĚĘÓƵ history.

It has been the backdrop for holiday concerts, dances, firework displays, midnight Homecoming traditions, purple-pancake breakfasts, fashion shows and Weber’s Juneteenth celebration.

In times of tragedy, such as the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Wildcats have gathered at Stewart Bell Tower to comfort each other and grieve as a community.

Hurst, who lives near campus, admits he misses daily carillon concerts. But, as he has watched Stewart Bell Tower retain its prominence amidst campus growth and development, he has grown increasingly proud of the role he played in securing a historic gift whose mere presence symbolizes the dignity and distinction associated with higher education.

“Over the years, there came a sense of pride in having done something that would outlive me,” said Hurst, who is 94. “I think what they’ve done to the plaza is absolutely marvelous. I’m sure the Stewarts would agree.”

About the Author

Most kids grow up hearing nursery rhymes and fairy tales at bedtime; former broadcast journalist Karin Hurst AA ’79 grew up listening to

her dad’s Weber State campus stories. Dean Hurst AS ’48 began an administrative career there in 1967 and retired as vice president for college relations in 1989. At 94, he’s one of the few, living primary sources of 91¶ĚĘÓƵ history. For Karin, now a writer for University Marketing & Communications, the 50th anniversary of Stewart Bell Tower seemed a perfect opportunity to plumb Dean’s treasure trove of first-hand knowledge.