A Step Up to Medical School

Clair Weenig BA ’65 vividly remembers the anxiety he felt arriving in San Francisco with only $10 and no place to stay, hoping to get into medical school.

Clair Weenig BA ’65 vividly remembers the anxiety he felt arriving in San Francisco with only $10 and no place to stay, hoping to get into medical school.

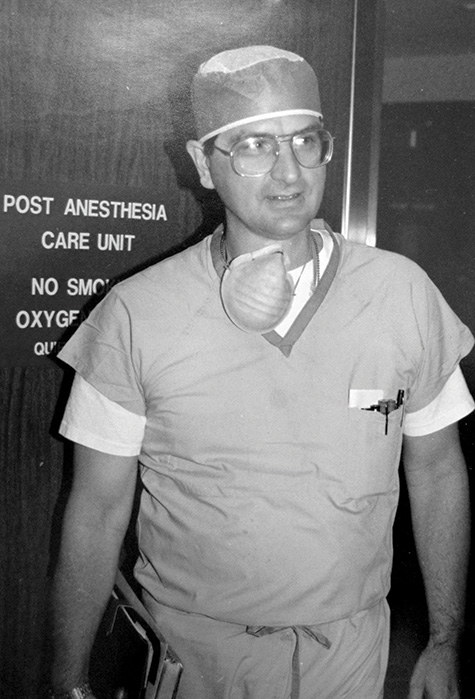

Knowing first-hand that even a little assistance can go a long way, Weenig, a successful anesthesiologist, funds a Weber State scholarship with his wife, Joan, that pays for students to apply and interview at medical schools. “Being in San Francisco without much in your pocket isn’t exactly a party,” he recalled. “I still can’t believe I pulled it off, but I did.”

After high school, a close friend urged Weenig to enroll at Weber Junior College. As the seventh of eight children, and with his father’s small meat market failing financially, it was apparent the family couldn’t afford higher education.

Nonetheless, Weenig took odd jobs to earn the $111 required for the first quarter.

A paper he wrote in a first-year English class caught the attention of E. Carl Green, Weber’s debate coach. He earned a spot on the debate team, along with a scholarship to continue his education. As the junior college officially became Weber State College, a four-year institution, Weenig decided to major in life science.

“Going to Weber State really was fortuitous for me,” Weenig said. “It was a very important springboard.”

While he originally planned to pursue law school, his advisor, Jennings G. Olson, recommended medical school because of his near 4.0 in math, physics, chemistry and other science courses, and very few courses geared toward law.

At the time, students applied to each medical school individually. Weenig remembers most application fees cost about $15. His family had lost their home and moved in with his grandfather on a farm in Plain City. While Weenig’s University of Utah application was free, he paid the application fees for Georgetown, Johns Hopkins and the University of Pennsylvania. With only $5 left, he had just enough to apply to the University of California, San Francisco as well.

At the time, students applied to each medical school individually. Weenig remembers most application fees cost about $15. His family had lost their home and moved in with his grandfather on a farm in Plain City. While Weenig’s University of Utah application was free, he paid the application fees for Georgetown, Johns Hopkins and the University of Pennsylvania. With only $5 left, he had just enough to apply to the University of California, San Francisco as well.

UCSF invited him to an interview; the only problem was paying for the trip.

Luckily, he found an affordable train ticket — $29 round trip from Salt Lake City.

Along with his $10, he brought a brown paper bag for his luggage and a shoe box with tuna sandwiches for provisions. In San Francisco, he realized most hotels cost $20 to $30 per night. Luckily, a stranger at the bus station told him his brother was the night watchman at a hotel he could stay in for only $8 — given that he checked in late and checked out before housekeeping made its rounds. This left Weenig with $2, enough to cover the fare for the trolley to and from campus the next day with change to spare.

Other interviewees at the UCSF dean’s office looked polished with their suits, ties, shined shoes and leather briefcases, a sharp contrast from Weenig’s humble attire and baggage. Still, he did his best through three interviews.

Four weeks later, he received a letter inviting him to join the UCSF medical school class of 1969. It also said he received a scholarship, covering his tuition and providing a $2,500 annual stipend.

After graduating from the university’s medical school, Weenig completed an internship at the University of Colorado Hospital in Denver, residency at the UCSF Medical Center and two years in the U.S. Navy. He began his practice as an anesthesiologist in Walnut Creek, California, and held numerous leadership positions. After 20 years in private practice, he entered academic practice and retired from UCSF in 2006 as a clinical professor emeritus in anesthesiology.

While Weenig looks back on his UCSF acceptance with a smile, he doesn’t want other pre-med students to face the same uncertainty he did walking into the dean’s office.

“I don’t want students to think ‘But I’m from this small town ...” he said. “I didn’t want them to feel intimidated and that they shouldn’t apply and wouldn’t be able to afford it.”

Now, students usually apply to about 10 medical schools through one company for a flat rate of around $200, with each additional school costing about $100 each. If a school shows interest, there’s a secondary application that costs around $100, and a subsequent application interview only means paying more, including travel costs.

Ben Packard graduated pre-med in December with a major in microbiology and dual minors in neuroscience and chemistry. He said the scholarship was incredibly helpful as applying to medical schools is expensive. He applied to about 30 schools.

Ben Packard graduated pre-med in December with a major in microbiology and dual minors in neuroscience and chemistry. He said the scholarship was incredibly helpful as applying to medical schools is expensive. He applied to about 30 schools.

“The scholarship was a huge blessing to be able to go through that process and not go into debt,” Packard said.

Drake Alton found out he had received the scholarship after already paying for his applications, so the ability to reimburse himself for those costs meant he had the money to travel and see which school he preferred in person. He ultimately chose Mayo Clinic’s Arizona location.

“Without [the scholarship] I don’t think I would have been able to visit those schools,” he said.

Weenig initially donated $10,000 to create the scholarship, which is now endowed with over $50,000 to award students.

Weenig initially donated $10,000 to create the scholarship, which is now endowed with over $50,000 to award students.

He named the scholarship after George Gregory, a professor of anesthesia at the University of California Medical Center, San Francisco, known for developing a treatment of respiratory failure in prematurely born babies whose lungs have not fully developed. Gregory also provided Weenig with invaluable training during his residency and served as a role model and mentor.

“One of my best friends has a daughter who weighed less than one kilogram; about two pounds. None of those babies survived back in the early days, and now she’s alive, a mother of two and a practicing nurse because of his technology,” Weenig said.

Since the endowment was created in 2004, 15 premed students have been awarded $15,298 total in scholarship money to assist with their medical school application expenses.

Thanks to the George Gregory scholarship, and other financial assistance, Brian Farnsworth graduated from 91短视频 debt-free before going to medical school at The Ohio State University. “That’s a much better place than some people are at when they start medical school,” he said.

Weenig also created a scholarship available to any 91短视频 student, and named it in honor of his grandfather, Henry Merwin Thompson, who provided a home during those lean financial years.

Weenig and his wife, Joan, have included 91短视频 in their estate plans, which will increase funding for the Gregory Scholarship and, hopefully, benefit premed students for many more years.

Weenig and his wife, Joan, have included 91短视频 in their estate plans, which will increase funding for the Gregory Scholarship and, hopefully, benefit premed students for many more years.

“THE SCHOLARSHIP WAS A HUGE BLESSING TO BE ABLE TO GO THROUGH THAT PROCESS AND NOT GO INTO DEBT.” — Ben Packard

“WITHOUT THE SCHOLARSHIP I DON’T THINK I WOULD HAVE BEEN ABLE TO VISIT THOSE SCHOOLS.” — Drake Alton

.